MOGADISHU (Kaab TV) – Somalia remains one of the most dangerous countries for journalists, with escalating threats from both the government and extremist groups.

In the first four months of 2025 alone, 46 journalists were detained across Somalia and Somaliland, according to the Somali Journalists Syndicate (SJS).

The climate of fear is further illustrated by the confiscation of equipment from at least 29 journalists during the same period—most of whom also had their footage and materials deleted.

Mogadishu stands out as the most perilous city for media professionals.

On March 18, journalist Mohamed Abukar Dabaashe was killed in a bomb attack near Villa Somalia, the presidential palace.

The attack was carried out by the militant group Al-Shabaab, which continues to target civilians and journalists through bombings and assassinations.

But journalists in Mogadishu are not only under threat from armed groups. Security forces—particularly the police and the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA)—routinely detain and intimidate reporters.

Of the 46 journalists detained since January, 41 were from Mogadishu alone. In Somaliland, five journalists were also arrested, and Universal TV was suspended—a ban that remains in effect.

The case of Risaala Radio highlights the dangers journalists face for simply doing their job. On March 18, shortly after the bombing, the station was raided by Mogadishu police, and 24 people were detained—including five journalists.

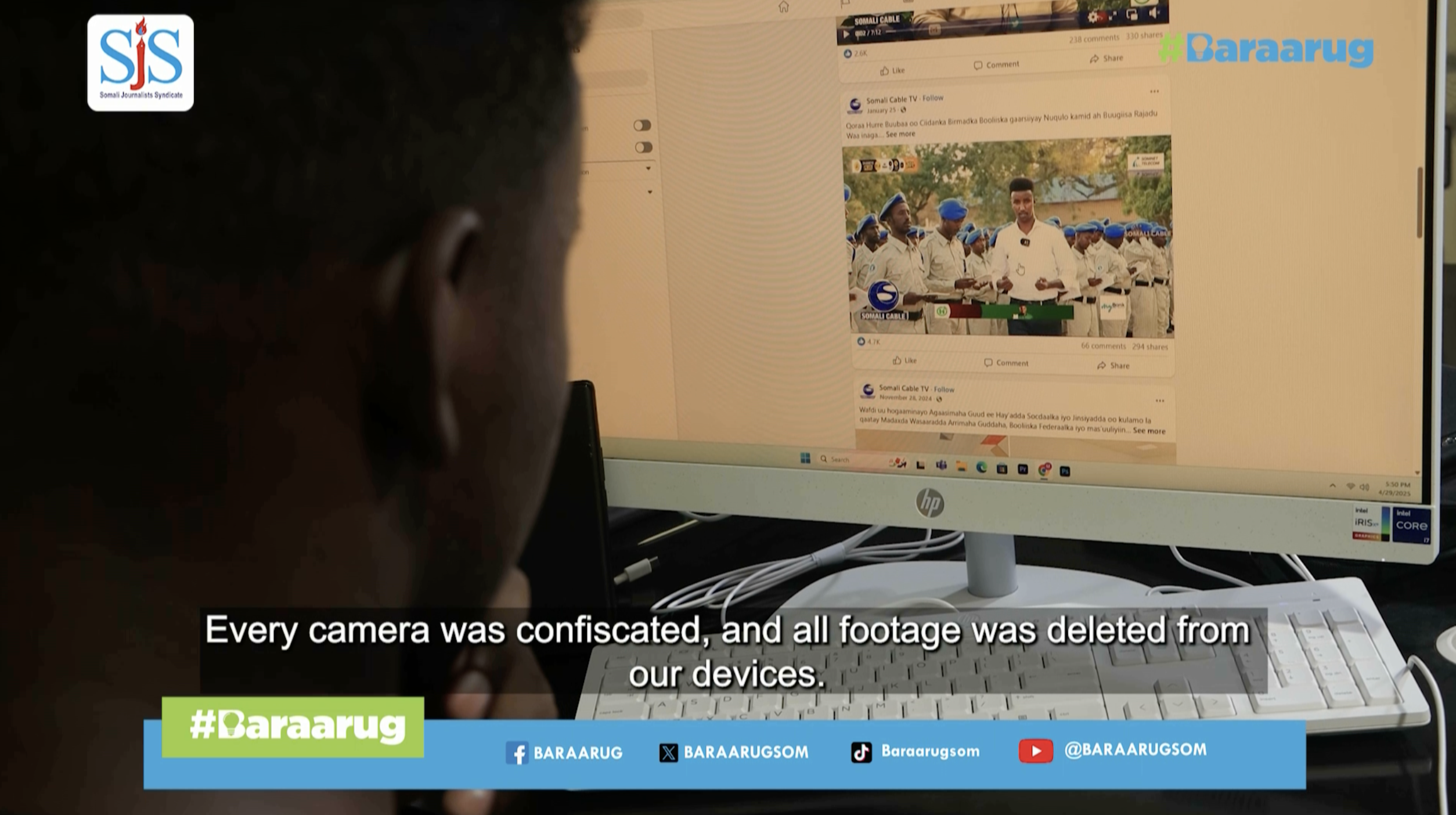

Abdihafid Nur, a journalist with Somali Cable TV, was among those arrested.

He had been reporting from the bombing site when police from the Mobile Checkpoints Unit detained them.

“By the time we reached the scene, the road had already been closed. We captured what we could. Then police arrived and forced us into a pickup truck. While in custody, we were ordered to delete all footage. Our cameras and devices were confiscated,” Nur recounted.

Ali Ibrahim Suheyfa, a journalist with Risaala Radio, was in the studio when the raid happened. The police were reportedly led by Abdi Ali, a former Al-Shabaab member now working with the authorities.

“We were the first radio station to broadcast news of the bombing targeting President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. Shortly after, the police stormed our offices and detained all of us,” Suheyfa said.

The station was shut down for several hours following the raid. After intense questioning, the five journalists were released.

“We returned to work, but fear gripped us. Some colleagues called their families, unsure if they’d be arrested again,” he added.

These acts of suppression extend beyond physical harassment.

Government officials, including those from the Ministry of Information, Ministry of Security, and the Banadir Police Commission, have openly threatened journalists.

On March 6, Minister of Information Daud Aweis warned that any journalist or member of the public who reported on security issues online would face arrest, punishment, and prosecution.

“We warn the media, social media users, and the public not to spread false information or distress regarding security,” he said.

That same day, Banadir Regional Police Commander Mahdi Omar Muumin—another ex-Al-Shabaab member now serving in government—threatened to detain journalists in “dark cells” if they reported on insecurity in Mogadishu.

“If [the journalist] is not bleeding now, we’ll make him sweat in a dark cell, God willing,” Polie commander Muumin declared.

Internet censorship has also become a tool for silencing critical voices. As traditional media outlets are suppressed, journalists increasingly rely on social media—especially Facebook—to report.

But even there, they face restrictions.

Between January and April, SJS documented at least eight cases where journalists had their Facebook accounts disabled or limited.

Mohamed Salah, founder of Ilsan Media in Puntland, was among those affected.

“My personal Facebook account was restricted for weeks. I received a message saying I was dead, and my page was marked as ‘memorialized,’” he said.

SJS contacted Meta, Facebook’s parent company, and eventually, Mohamed’s page—and those of other journalists—were restored. However, Meta never publicly acknowledged the issue.

Female journalists face even greater risks, including gender-based threats and workplace harassment.

Bahjo Abdullahi Salad was arrested on March 15 after posting a video showing rubbish left on the streets by officials at the Prime Minister’s Office.

“Early that morning, they arrested me and accused me of working with terrorists. I was forced to delete the video. It was only after my family intervened and fellow journalists protested that I was released,” Bahjo said. “But even now, NISA agents continue to monitor me.”

SJS Secretary General Abdalle Mumin denounced the ongoing attacks on journalists by both state forces and Al-Shabaab.

“It is unacceptable that both the terrorist group and Somali security forces—many of whom are former Al-Shabaab members—are targeting journalists, especially in Mogadishu,” he said. “We call for immediate action at national and international levels to protect journalists, hold perpetrators accountable, and safeguard media freedom.”